Context: In 2017, I presented a keynote at IXDA Florianópolis that proposed something most people weren't talking about yet: what if digital products could adapt to you the way a good teacher, coach, or friend does? Not just remember your preferences, but actually notice your struggles, recognize your patterns, and adjust in real time to help you grow.

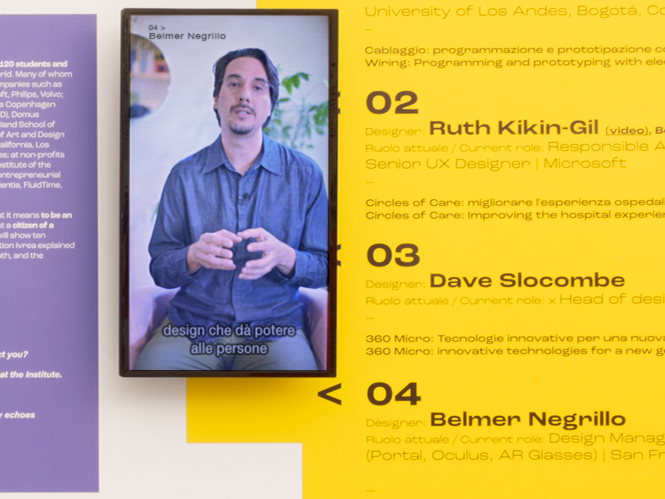

Presenting the concept of Adaptive UX in 2017 to an audience of 1500 people.

I never got as concrete with this concept as in my work with the Lemann Foundation on teaching literacy in Brazilian public schools. We faced the challenge of turning static, one-size-fits-all education materials into a platform that dynamically adjusts in real time to individuals and supports learning goals.

The core idea: ask a dynamic set of spelling exercises, and treat errors as windows into a kid's understanding of the written system at that moment. Use those signals to create targeted exercises that would promote a conflict with their incorrect or incomplete understanding, triggering a redefinition that requires them to incorporate new knowledge and evolve their mental model.

Not too different from how scientific theories evolve.

This solution was grounded in observing teachers with 25 years of experience and manually encoding their tacit knowledge into software. We taught the system to interpret unconventional spellings as evidence of specific learning hypotheses—like a child believing "big animals should have big names"—and mapped the different ways those teachers personalized their tutoring based on that evidence. For example, asking the child to spell small names of big animals, and large names of small animals.

Asking the child to spell small names of big animals and large names of small animals challenges an incomplete mental model.

Some principles of Adaptive UX.

We create mental models of what intelligence is, which often lead to expectations that are not fulfilled by what a machine can do.

Design can reduce that gap by clearly communicating the right expectations and enhancing the experience's value. Al does not need to be super-intelligent to be useful. It can achieve great results by properly collaborating with people.

A collaborative editor starts by diagnosing what you want to write, the style, your proficiency level, and how engaged you are with the task. For example, analyzing how you start the text, the phrases you write, how decisive you are in writing, and even the inspiration you gathered before starting to write. And validating with transparency: Did I get this right?

It is the design of a relationship between AI and people, grounded on empathy, trust, and collaboration.

The full keynote presentation, 52 min.